On the 24th of may (2019), SpaceX launched a Falcon 9 rocket filled with 60 satellites into space. This marks the beginning of their ambitious new project called “Starlink” which aims to provide high quality broadband internet to the most isolated parts of the planet, while also providing low latency connectivity to already well connected cities.

SpaceX aim to make their broadband as accessible as possible, claiming that anyone will be able to connect to their network if they buy the pizza box-sized antenna which SpaceX is developing themselves.

This launch of 60 satellites, was just the first of many. Spacex has 12,000 satellites planned for launch over the next decade, dramatically increasing the total amount of spacecraft around Earth’s orbit. This will cost SpaceX billions of dollars, so they must have a good reason for doing so. Let’s see how this network will work, and how it will compete with existing internet providers.

Back in 2015, Elon announced that SpaceX had began working on a communication satellite network, stating that there is a significant unmet demand for low-cost global broadband capabilities. Around that time, SpaceX opened a new facility in Redmond, Washington to develop and manufacture these new communication satellites.

The initial plan was to launch two prototype satellites into orbit by 2016 and have the initial satellite constellation up and running by 2020. But the company struggled to develop a receiver that could be easily installed by the user for a low cost, this delayed the program and the initial prototype satellites weren’t launched until 2018.

After a successful launch of the two prototypes, Tintin-A and B, which allowed SpaceX to test and refine their satellite design, SpaceX kept pretty quiet about what was next for the Starlink project, until November 2018 when SpaceX received the approval from the FCC to deploy 7,500 satellites into orbit, on top of the 4,400 that were already approved.

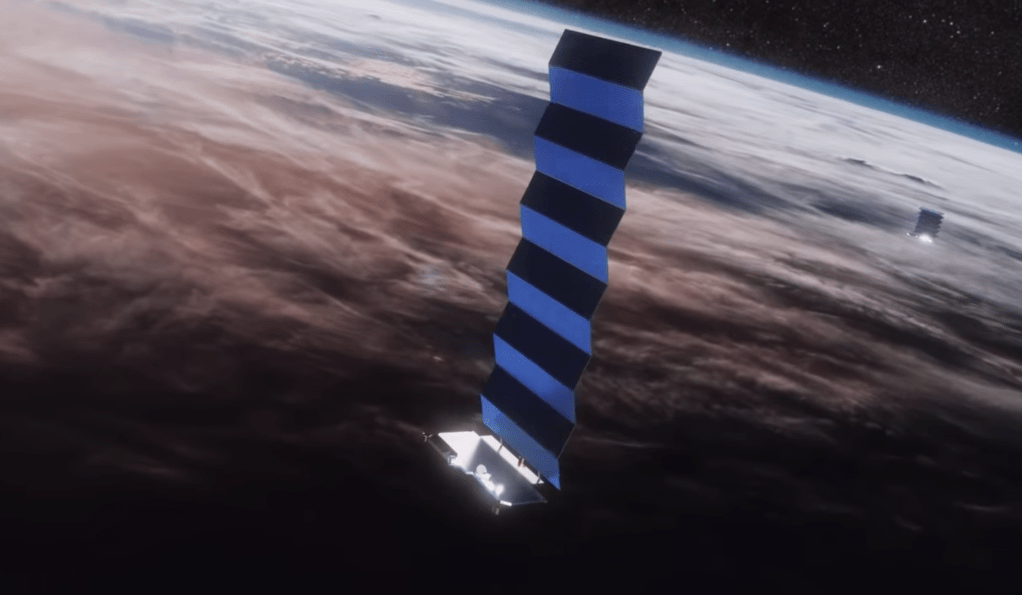

On May 24th 2019, the first batch of production satellites were launched into orbit and people around the world quickly started to spot the train of satellites moving across the night sky. This launch is a sign of things to come, while this initial group of satellites are not fully functional, they will be used to test things like the earth communications systems and the krypton thrusters which will be used to autonomously avoid debris and de-orbit Let’s look at these functionalities first.

We have explored how ion thrusters work in the past, which you can watch for more detail, but essentially they use electric potential to fire ions out of the spacecraft to provide propulsion. Xenon is ideally used, because it has a high atomic mass allowing it to provide more kick per atom, while being inert and having a high storage density lending itself to long term storage on a spacecraft.

However SpaceX opted for krypton, as xenon’s rarity makes it a far more expensive propellant. This ion thruster will initially be used to raise the starlink satellites from their release orbits at 440 km to their final orbital height of 550 km.

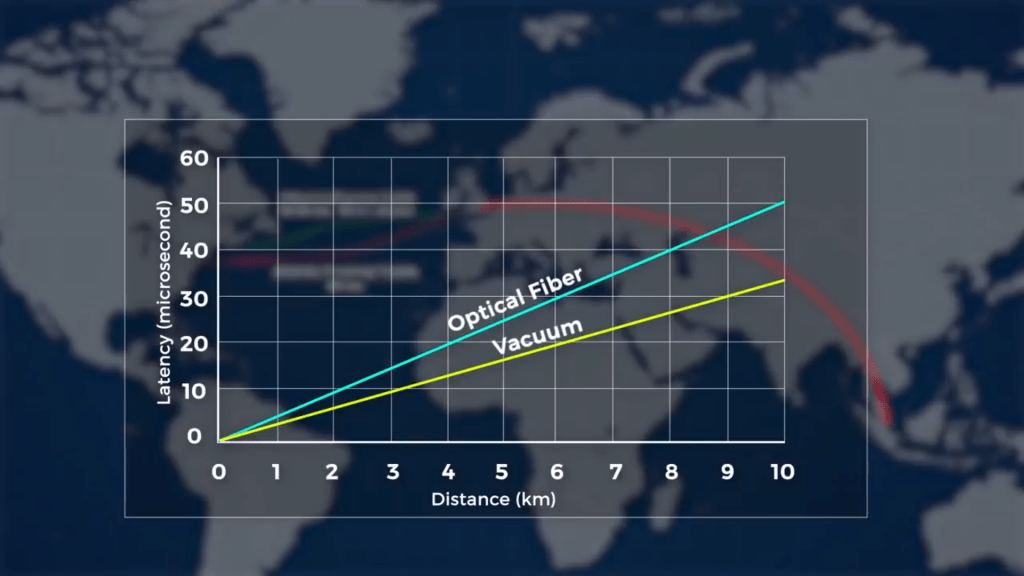

In a vacuum light travels at a speed of 299,792,458 meters per second. The speed of travel in glass depends on the refractive index and the refractive index depends on wavelength, but we will take the reduction as 1.47 times slower than the speed of light in a vacuum [203940448 m/s]. This means the data packet will take roughly 0.063 seconds to make the round trip, and thus has a latency of 0.063 seconds, or 62.7 milliseconds.

With the additional steps that add to this latency like the conversion of light signals to electrical signals on either end of the optical cable, traffic queues, and the transfer to our final computer terminal, this total time comes out at about 76 milliseconds. Figuring out the latency for Starlink is a lot more difficult, as we have no real world measurements to go by, but we can make some educated guesses with the help of Mark Handley, a communications professor in University College London.

The first source of latency for Starlink will be during the up and down link process, where we need to transfer our information to and from earth. We know this will be done with phase array antenna, which are radio antenna that can control the direction of their transmission without moving parts, instead they use destructive and constructive interference to control the direction of the radio wave.

Each satellite has a cone beam with a 81 degree range of view. With an orbit of 550 kilometres each satellite can cover a circular area with a radius of 500 kilometre. At SpaceX’s originally planned orbit this coverage had a radius of 1060 kilometres. Lowering the altitude of a satellite decreases the area it can cover, but also decreases the latency. This is particularly noticeable for typical communications satellites operating in geostationary orbit at an altitude of about 36,000 kilometres. The time it takes data to travel up to the satellite and back down travelling at the speed of light is around 240 milliseconds 369% slower than our subsea cable. However, since Starlink is intending to operate at a much lower altitude, the up and down link theoretical latency could be as low as 3.6 ms. This is why SpaceX needs so many satellites in their constellation in order to provide worldwide coverage.

This directional beam was an essential part of SpaceX’s FCC approval application, as thousands of satellites broadcasting undirected radio waves would cause significant amounts of interference with other communication methods. Once that data is received by one starlink satellite, it can begin to transmit that information between satellites using lasers. Each time we hop from satellites there will be a small delay as the laser light is converted to an electric signal and back again, but it is too miniscule to consider. Things get tricky here with using lasers, as we need to accurately hit the receiver on neighbouring satellites to transmit that data.

Let’s look at SpaceX’s proposed constellation to see how this will work. Space X’s first phase of 1584 satellites will occupy 24 orbital planes, with 66 satellites in each plane inclined at 53 degrees.

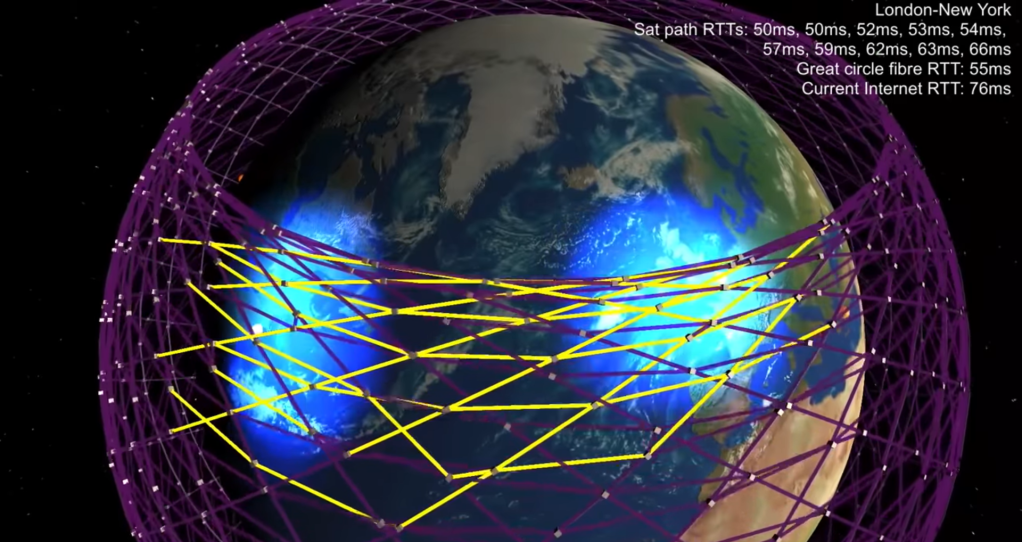

Communication between neighbouring satellites in the same orbital plane is relatively simple, as these satellites will remain in relatively stable positions in relation to each other. This gives us a solid line of communication along a single orbital plane, but in many cases a single orbital plane will not connect two locations, so we need to be able transfer information between these planes too.

This requires precise tracking, as the satellites travelling in neighbouring orbital planes are travelling incredibly quickly and will come in and out of view. This means the starlink satellite will need to switch to a new satellite in the network.

This can take time, the best figure I could find is about a minute for the European Space Agency’s Data Relay Satellite System, which is a currently operating geostationary internet constellation designed to serve european imaging satellites, and other time critical applications. Such as serving emergency forces in remote areas, like those fighting forest fires. Starlink may be faster, but it won’t be instantaneous, and thus it has 5 optical communication systems on board to maintain a steady connection to 4 satellites at all times.

If we now use this system, transmitting from New York to London and back, with the shortest path possible, using the speed of light in a vacuum as our transfer speed, we can achieve a latency as low as 43 milliseconds. Even if we took the shortest route possible with an optic fibre, which does not exist, this would take about 55 milliseconds, a 28% decrease in speed.

The actual current return trip time for your average Joe is about 76 milliseconds, as we saw earlier. A 77% decrease in speed. This is a huge deal for the two financial markets working out of these cities, with millions of dollars being moved in fractions of a second, having a lower latency would provide a massive advantage in capitalizing on price swings. In fact, it wouldn’t be the first time a communications company has made a massive investment to specifically serve these groups.

At a cost of 300 million dollars this 5 millisecond increase in speed was justified to just connect across the Atlantic. Imagine how much these time sensitive industries will be willing to pay for a 17 millisecond increase in speed. It becomes even more valuable when you realize this time differential increases with increased transmission distance. New York to London is a relatively short distance.

The improvements would be even more pronounced for a London to Singapore transmission, for every additional kilometer we travel the potential gains in speed increase rapidly. But SpaceX aren’t just planning on serving this super fast internet to some customers, they primarily advertise this system as a way to connect every human on this planet to the internet, and they should have plenty of bandwidth left over to serve these people.

How much it will cost ?

Although the internet has been one of the fastest growing technologies in human history, by the end of 2019 more than half of the world’s population will still be offline (4 billion). Users will connect to this internet using a Starlink terminal which will cost around $200 each, this will still be far outside the purchasing power of many third world citizens, but it’s a start and vastly cheaper then similar currently available receivers like the Kymeta version at a price of $30,000.

Elon Musk says that these will be flat enough to fit onto the roof of a car and other vehicles like ships and airplanes. This will allow Starlink to compete with traditional internet providers. It’s estimated that moving the US from a 4G to a 5G wireless connection will cost around $150 billion in fiber optic cabling alone over the next 7 years, SpaceX plan to complete their entire Stralink project for as little as $10 billion.

Each Starlink satellite cost around $300,000 which is already a massive cut in cost for communication satellites.

SpaceX are also saving on launch costs, as they are launching on their own Falcon 9 rocket, something that no other satellite manufacturer has. If everything goes to plan, Starlink is estimated to generate $30 billion to $50 billion in revenue each year on the back of premium stock exchange memberships, demolishing their current annual revenue of around $3 billion.

And this is a vital part of Elon Musk’s long term goals. The money generated from Starlink will mean SpaceX will have vastly more funding than NASA. Which could go on to fund research and development of new rockets and the technology needed to monetise lunar and martian colonies. For now the project is simply connecting the world even more and potentially opening avenues for education for third world countries that do not have adequate connections to the internet.

Starlink hopes to offer internet speeds of 1,000 Mbps, comparable to 5G (about 1,400 Mbps). However, to provide the blazing fast connection speeds Starlink is promising, it needs to have ground transceivers — small terminals mounted on customers’ homes or businesses, analogous to satellite dishes. That’s where Tesla comes in — Smarter Analyst speculates that Starlink could use Tesla vehicles as ground transceivers, reducing the number of antennas that need to be installed in areas where Tesla cars are present. Tesla vehicles will probably be outfitted with receptors connected to the Starlink satellites to provide fast and reliable in-car Wi-Fi. However, the receptor could also be built as a transceptor, allowing each Tesla vehicle not only to receive a signal, but to act as a local Wi-Fi hotspot.